For those not familiar with Robert Kaplan, he is one of the ideological guides of the Neo-Conservatives. He is an unabashed advocate of United States Imperialism and proposes policies that would extend and strengthen empire of the United States.

This first op-ed was written by Robert Kaplan and appeared in the editorial section of the Wall Street Journal. In an earlier post, we noted that George Bush had used the term "Indian Country" when addressing the audience gathered for the NMAI opening. "Indian Country" has various legal and political definitions but it also is a term used in the military. Robert Kaplan explains how the term "Indian Country" fits into his ideological framework.

The second commentary is a response from Shawnee scholar, Steve Newcomb.

War on Terrorism

Indian Country

By Robert D. Kaplan

The Wall Street Journal

September 21, 2004

An overlooked truth about the war on terrorism, and the war in Iraq in particular, is that they both arrived too soon for the American military: before it had adequately transformed itself from a dinosauric, Industrial Age beast to a light and lethal instrument skilled in guerrilla warfare, attuned to the local environment in the way of the 19th-century Apaches. My mention of the Apaches is deliberate. For in a world where mass infantry invasions are becoming politically and diplomatically prohibitive -- even as dirty little struggles proliferate, featuring small clusters of combatants hiding out in Third World slums, deserts and jungles -- the American military is back to the days of fighting the Indians.

The red Indian metaphor is one with which a liberal policy nomenklatura may be uncomfortable, but Army and Marine field officers have embraced it because it captures perfectly the combat challenge of the early 21st century. But they don't mean it as a slight against the Native North Americans. The fact that radio call signs so often employ Indian names is an indication of the troops' reverence for them. The range of Indian groups, numbering in their hundreds, that the U.S. Cavalry and Dragoons had to confront was no less varied than that of the warring ethnic and religious militias spread throughout Eurasia, Africa and South America in the early 21st century. When the Cavalry invested Indian encampments, they periodically encountered warrior braves beside women and children, much like Fallujah. Though most Cavalry officers tried to spare the lives of noncombatants, inevitable civilian casualties raised howls of protest among humanitarians back East, who, because of the dissolution of the conscript army at the end of the Civil War, no longer empathized with a volunteer force beyond the Mississippi that was drawn from the working classes.

Indian Country has been expanding in recent years because of the security vacuum created by the collapse of traditional dictatorships and the emergence of new democracies -- whose short-term institutional weaknesses provide whole new oxygen systems for terrorists. Iraq is but a microcosm of the earth in this regard. To wit, the upsurge of terrorism in the vast archipelago of Indonesia, the southern Philippines and parts of Malaysia is a direct result of the anarchy unleashed by the passing of military regimes. Likewise, though many do not realize it, a more liberalized Middle East will initially see greater rather than lesser opportunities for terrorists. As the British diplomatist Harold Nicolson understood, public opinion is not necessarily enlightened merely because it has been suppressed.

I am not suggesting that we should not work for free societies. I am suggesting that our military-security establishment be under no illusions regarding the immediate consequences.

In Indian Country, it is not only the outbreak of a full-scale insurgency that must be avoided, but the arrival in significant numbers of the global media. It would be difficult to fight more cleanly than the Marines did in Fallujah. Yet that still wasn't a high enough standard for independent foreign television voices such as al-Jazeera, whose very existence owes itself to the creeping liberalization in the Arab world for which the U.S. is largely responsible. For the more we succeed in democratizing the world, not only the more security vacuums that will be created, but the more constrained by newly independent local medias our military will be in responding to those vacuums. From a field officer's point of view, an age of democracy means an age of restrictive ROEs (rules of engagement).

The American military now has the most thankless task of any military in the history of warfare: to provide the security armature for an emerging global civilization that, the more it matures -- with its own mass media and governing structures -- the less credit and sympathy it will grant to the very troops who have risked and, indeed, given their lives for it. And as the thunderous roar of a global cosmopolitan press corps gets louder -- demanding the application of abstract principles of universal justice that, sadly, are often neither practical nor necessarily synonymous with American national interest -- the smaller and more low-key our deployments will become. In the future, military glory will come down to shadowy, page-three skirmishes around the globe, that the armed services will quietly celebrate among their own subculture.

The goal will be suppression of terrorist networks through the training of -- and combined operations with -- indigenous troops. That is why the Pan-Sahel Initiative in Africa, in which Marines and Army Special Forces have been training local militaries in Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Chad, in order to counter al-Qaeda infiltration of sub-Saharan Africa, is a surer paradigm for the American imperial future than anything occurring in Iraq or Afghanistan.

In months of travels with the American military, I have learned that the smaller the American footprint and the less notice it draws from the international media, the more effective is the operation. One good soldier-diplomat in a place like Mongolia can accomplish miracles. A few hundred Green Berets in Colombia and the Philippines can be adequate force multipliers. Ten thousand troops, as in Afghanistan, can tread water. And 130,000, as in Iraq, constitutes a mess that nobody wants to repeat -- regardless of one's position on the war.

In Indian Country, the smaller the tactical unit, the more forward deployed it is, and the more autonomy it enjoys from the chain of command, the more that can be accomplished. It simply isn't enough for units to be out all day in Iraqi towns and villages engaged in presence patrols and civil-affairs projects: A successful FOB (forward operating base) is a nearly empty one, in which most units are living beyond the base perimeters among the indigenous population for days or weeks at a time.

Much can be learned from our ongoing Horn of Africa experience. From a base in Djibouti, small U.S. military teams have been quietly scouring an anarchic region that because of an Islamic setting offers al Qaeda cultural access. "Who needs meetings in Washington," one Army major told me. "Guys in the field will figure out what to do. I took 10 guys to explore eastern Ethiopia. In every town people wanted a bigger American presence. They know we're here, they want to see what we can do for them." The new economy-of-force paradigm being pioneered in the Horn borrows more from the Lewis and Clark expedition than from the major conflicts of the 20th century.

In Indian Country, as one general officer told me, "you want to whack bad guys quietly and cover your tracks with humanitarian-aid projects." Because of the need for simultaneous military, relief and diplomatic operations, our greatest enemy is the size, rigidity and artificial boundaries of the Washington bureaucracy. Thus, the next administration, be it Republican or Democrat, will have to advance the merging of the departments of State and Defense as never before; or risk failure. A strong secretary of state who rides roughshod over a less dynamic defense secretary -- as a Democratic administration appears to promise -- will only compound the problems created by the Bush administration, in which the opposite has occurred. The two secretaries must work in unison, planting significant numbers of State Department personnel inside the military's war fighting commands, and defense personnel inside a modernized Agency for International Development.

The Plains Indians were ultimately vanquished not because the U.S. Army adapted to the challenge of an unconventional enemy. It never did. In fact, the Army never learned the lesson that small units of foot soldiers were more effective against the Indians than large mounted regiments burdened by the need to carry forage for horses: whose contemporary equivalent are convoys of humvees bristling with weaponry that are easily immobilized by an improvised bicycle bomb planted by a lone insurgent. Had it not been for a deluge of settlers aided by the railroad, security never would have been brought to the Old West.

Now there are no new settlers to help us, nor their equivalent in any form. To help secure a more liberal global environment, American ground troops are going to have to learn to be more like Apaches.

link to article

This is Steve Newcomb's response. At this point, we have not web link for it but will provide one when it becomes available on the internet.

Indian Country As “Enemy Territory”

Steven Newcomb, Columnist

On September 21, the day some 20,000 American Indian representatives gathered in Washington, D.C. to celebrate the grand opening of the National Museum of the American Indian, the Wall St. Journal decided publish a column by Robert D. Kaplan, based on the background metaphor Indian Country is Enemy Territory.

Kaplan’s article is entitled “Indian Country.” He uses the term “Indian Country” to frame and illustrate a number points he wants to make about “the war on terrorism and the war in Iraq in particular.”

For example, Kaplan says that as “dirty little struggles proliferate, featuring small clusters of combatants hiding out in Third World slums, deserts and jungles—the American military is back to the days of fighting the Indians.”

Since the United States government and the U.S. military are said to be fighting “terrorists,” another background metaphor Kaplan uses can be expressed as a simile: Fighting present day “terrorists” is like a return to the days when the U.S. was fighting Indians in the “Old West.” Flip the analogy around, and our Native ancestors who resisted the advance of the United States are being compared to present day “terrorists” and “insurgents.”

In a previous discussion of American pathological attitudes and behavior towards Native peoples, this column explained that metaphors are used to think of one thing in terms of another. Kaplan claims that the “red Indian metaphor…captures perfectly the combat challenges …[faced by the American military in] the early 21st century.” Thus, the combat challenges that the U.S. military is facing in the Middle East and in other areas of the world, are being thought of in terms of the combat challenges that U.S. military once faced in its wars against Indian nations during the expansion of the American empire across the West.

In other words, Kaplan is thinking of the U.S. “war against terrorism” and the U.S. “war in Iraq in particular” in terms of the U.S. war against “Indian Country” in the latter decades of the nineteenth century.

There are two main steps to this kind of metaphorical thinking. First, think of features and characteristic of the U.S. war against Indian nations in the West in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Second, imaginatively apply those characteristics to what U.S. military is now attempting to accomplish against its enemies abroad.

To balance our comparison, the word “enemies” is a term that needs to be applied to both the present day context and to the Indians of the past. Thus, there are two conceptual metaphors behind Kaplan’s use of “Indian Country” for his column:

1) Indians Are Enemies, and, 2) Indian Country is Enemy Territory. Enemies are those who are hostile to the way the U.S. defines its interests, some of whom are willing to oppose the U.S. militarily, and the category “enemy territory” is any region where such people live or are located.

To slightly soften his comparison, Kaplan reassures us that the comparison he is making is inspired by the U.S. military’s “reverence for” Indian enemies of old. In other words, Kaplan apparently wants us to know that the U.S. military now has “a feeling or attitude of deep respect tinged with awe” for the prowess of Indian enemy combatants of the past.

Kaplan sees a number of similarities between the past and the present. In the past, Kaplan says that the U.S. military’s job was to confront a wide “range of Indian groups, numbering in their hundreds.” The varieties of Indians, says Kaplan, “was no less varied than that of the warring ethnic and religious militias spread throughout Eurasia, Africa and South America in the early 21st century,” which, in Kaplan’s mind is the geographical scope of the “war on terror.”

Kaplan also sees that “civilian casualties” was an issue in the past, just as it is in the present. Thus: “When the Cavalry invested Indian encampments, they periodically encountered warrior braves beside women and children, much like Fallujah.”

Kaplan’s use of the word “invested” is certainly appropriate for a Wall St. Journal readership,” but in a military context the term means, “to surround a place with military forces so as to prevent approach or escape.”

Invest also means, “to besiege.” Siege is “the act or process of surrounding and attacking a fortified place,” but also, “any prolonged or persistent effort to overcome resistance.” Under “lay siege to” my dictionary provides the following example: “The invaders laid siege to the city for over a month.” Thus, Kaplan’s use of the term “invest” has metaphorically framed the U.S. Cavalry of the past as an invading force against Indian villages.

However, Kaplan reassures us that when the U.S. cavalry surrounded Indian encampments, “most Cavalry officers tried to spare the lives of noncombatants,” yet “inevitable civilian casualties” resulted, which “raised howls of protest among humanitarians back east.”

The massacre at the Washita River is a prime example of “inevitable civilian casualties” during nineteenth century U.S. military actions against Indian people. At dawn, on November 27, 1868, the 7th Cavalry attacked the tipi encampment of Black Kettle, a Cheyenne Peace Chief. The attack occurred under the command of Colonel George Armstrong Custer, who was responsible for the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre. Custer was under orders from General Phil Sheridan “to proceed south in the direction of the Antelope Hills, thence toward the Washita River, the supposed winter seat of the hostile tribes; to destroy their villages and ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, and bring back all women and children.”

At dawn, Custer’s troops attacked the camp on the Washita. In no time at all, the deadly fire from the soldiers guns cut down 103 “hostiles,” only 11 of whom were warriors. In other words, Custer’s troops killed 92 women and children. “Inevitable civilian casualties” resulted from the U.S. soldiers indiscriminately killing Cheyennes. The soldiers also gunned down several hundred horses. The horse was at the heart of the Cheyennes way of life and economy. The bullets that killed the horses was just another way of firing into the hearts of the Cheyennes.

Custer and his troops returned to Camp Supply where Sheridan was waiting. They marched in a procession, waving the scalps of Black Kettle and other massacred Cheyennes. A band played triumphant music. The soldiers with them 53 captured Cheyenne women and children. Sheridan praised Custer for “efficient and gallant services.”

Elsewhere in his column, Mr. Kaplan refers to “the American imperial future,” which, of course, correctly suggests an “American imperial past and present.” In my view, the metaphor of the American Empire is the frame needed to understand Kaplan’s use of the metaphor “Indian Country,” and to make sense of his comparison between the unjustifiable past actions of the U.S. against Indian nations and the U.S.’s current unjustifiable war in Iraq. Imperialism is its own justification.

His reference to America’s “imperial future,” infers that it was during America’s imperial past that the Plains Indians were, in Kaplan’s view, “ultimately vanquished” by “a deluge of settlers aided by the railroad.” If not for settlers and railroads, Kaplan suggests, the U.S. never could have been victorious in the Old West. He somehow fails to mention the U.S.’s intentional slaughter of the Indian communities, and the wholesale slaughter of the buffalo in order to destroy the food supplies and economic strength of the Plains Nations.

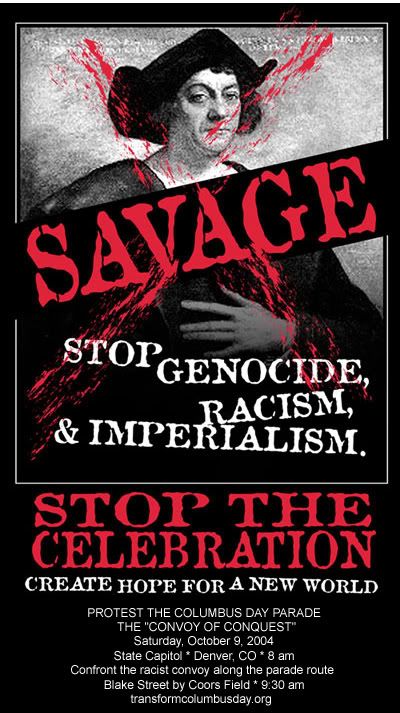

I understand the ending of Kaplan’s article in the following way: because there will be “no new settlers to help” the U.S. realize its “imperial future” in other parts of the world, “American ground troops are going to have to learn to be more like Apaches.” That Kaplan’s comparison here is weak, and ineffectual is illustrated by a photograph of Geronimo and a number of other Apache warriors brandishing rifles, with a present day photo caption that reads: “Fighting Terrorism Since 1492.”

The cognitive model for this photograph is familiar to every Native person who knows the history of what has been done by the United States to terrorize, kill off, and dispossess our ancestors, such as at the Washita River. Kaplan’s analogy doesn’t work because the Apaches were a key part of the resistance to the American empire for some twenty-five years.